2021 marks CHN’s 40th anniversary. We are truly proud of the hundreds of thousands of lives we have changed over the past 40 years, whether through connecting low-income families to affordable homeownership, building supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness or providing financial education and community resources for people experiencing housing instability. Over the next several weeks, we will be highlighting pivotal points in CHN’s history on our blog. Please tune in as we explore this rich history of believing in the power of a permanent address. This week’s post provides an overview of the historical context in which CHN was founded, and was greatly informed by an interview with our first Executive Director, Chris Warren.

If you want to understand CHN Housing Partners and how it evolved over the forty years since its founding as Cleveland Housing Network, you have to start with the world into which it was born.

The period preceding CHN’s founding in 1981—bracketed by the Hough Uprising in 1966 and the City of Cleveland’s municipal default in 1979—had been one of the most difficult in Cleveland’s history. When the 1970s began, Cleveland was home to more than three-quarters of a million people. By the time the 1970s had ended, almost one out of four of those people had moved elsewhere. While manufacturing employment had peaked in Cleveland in 1969, by the early 1980s, it had declined by a third.

Mid-20th Century, “urban renewal” practices and highway projects repeatedly displaced Cleveland’s African-American residents. A combination of discriminatory banking, real estate, and public housing practices then drove them into the city’s already densely populated east side neighborhoods. As a result, by the mid-1960s, 90% of Cleveland’s African-American population lived on the city’s east side, in neighborhoods and homes that had been neglected or ignored for years.

On both sides of the city, neighborhoods that had been precarious when the 1970s began were thoroughly devastated by the decade’s end. The City of Cleveland adopted a strategy of demolishing abandoned homes, collapsing structures into their basements, and covering them with dirt.

Entrepreneur “Daffy” Dan Gray summed up living in Cleveland during the 1970s on a popular t-shirt from the time: “Cleveland—You’ve got to be tough.”

For one group of Clevelanders, though, you had to be more than tough. They insisted Cleveland could do more than just take the beating the universe seemed set on delivering. Cleveland could fight back.

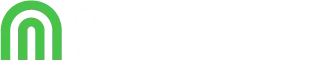

These activists saw what was happening to their city in granular detail: how abandoned homes were being demolished and not replaced, how slum lords were exploiting low-income people with exorbitant rents for properties that were barely livable, how neglect and corruption were rendering the places where they and their families lived almost uninhabitable. With an ethos combining the practicality of labor and community organizing and the idealism movements from the Sixties, they went to work.

Chris Warren came out of this movement to reclaim and rebuild Cleveland’s neighborhoods. As a community organizer for Tremont’s Merrick House, Chris drew together Tremont residents house-by-house and street-by-street. They advocated for improved services and infrastructure, better management of the Valley View Estates public housing complex, and redress of other grievances. Chris organized residents into the Tremont Neighborhood Tenants, which spurred the prosecution of particularly egregious landlords. And he and other residents formed one of Cleveland’s first Community Development Corporations (CDCs), Tremont West Development Corporation.

Chris wasn’t alone in taking this approach. Similar efforts were underway in the Glenville, Broadway, Near West, and St. Clair-Superior neighborhoods. Like Tremont, these four neighborhoods had also launched CDCs by the late 1970s.

In Hough, though, one group was focusing more on charity than activism. Sister Henrietta Gorris organized Famicos as a volunteer charity in the late 1960s, providing the basic needs of food, clothing, and shelter following the Hough Uprising. They also helped residents make basic home repairs. Sister Henrietta regularly exhorted Hough residents, “Don’t move. Improve!”

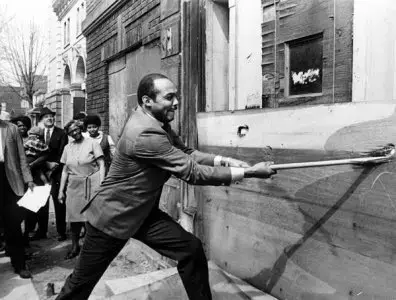

Famicos, under the leadership of its volunteer director, Bob Wolf, identified housing as a central element of neighborhood revitalization. According to Wolf, “It was determined after considerable study that a basic building block in a program to set the lives of the destitute on a course of recovery was the provision of adequate housing” (http://progressivecities.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/Yin-Community-Developmnet-in-Cleveland-Dissertation-Chapter.pdf). It was Bob Wolf who developed the innovation that spurred the creation of CHN and everything that followed—the Lease-Purchase approach to affordable housing.

Land contracts had been used for years as a way for property-owners—primarily white property owners—to steal wealth from low-income families—primarily Black and brown families—who desperately wanted to own their own homes.

Until more recent decades, most African-American families were routinely denied home mortgages; discriminatory redlining was a legal, accepted policy, and Black families were often forced to rent their homes. Unscrupulous landlords would dangle the possibility of eventually purchasing a home to lure families into signing rental agreements. These contracts mandated huge down payments and high rents, designed to take as much of each family’s money as quickly as possible. The requirements of these contracts were almost impossible to meet. Signing a land contract meant you could be evicted for one late payment of rent. As renters, land contract signatories had no equity in their homes. They found themselves on the street with no money and no recourse while the landlords moved on to their next victims.

Bob Wolf’s innovation was to turn the land contract on its head—or rather, have it live up to its promise. Under Wolf’s leadership, Famicos purchased

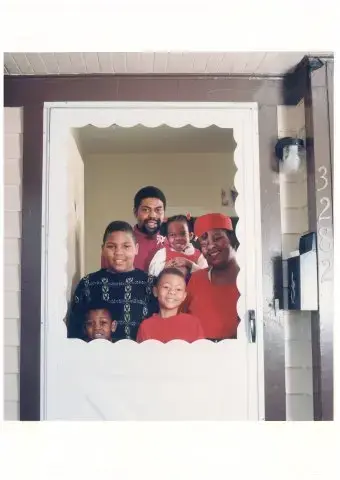

condemned, abandoned, and vacant homes, rehabilitated them, and leased them to aspiring homeowners with lower incomes, who could buy their home at the end of the lease’s 15-year term. The local Catholic Church, along with charitable organizations and banks, helped fund Famicos’ efforts, and by 1980 they had rehabilitated 200 units and built ten new homes.

Famicos started its lease-purchase efforts in the early 1970s, and by the late 1970s, five nascent CDCs began to emulate Famicos and learn from its example. In 1977, the leaders of the six organizations began meeting two to three times a week as the Lease-Purchase Operations Committee, which relied heavily on the expertise of Jim and Barbara Williams and Bob Wolf from Famicos. Along with Chris Warren from Tremont, other committee members included Bob Hudecek from Near West, Bob Pollock from St. Clair-Superior, Bobbie Reichtell from Broadway, and Hugh Gaines from Glenville. The five CDCs gradually began taking on houses with Famicos’ support, and from 1977-1980, the groups rehabbed and leased roughly 60 houses. The groups learned as they went, putting together systems to make the process of purchasing, rehabbing, and leasing homes more efficient. And they worked together to persuade the City to invest more capital in the program so it could expand.

In 1979, the Operations Committee hired Rosalyn Block as its coordinator. With Rosalyn facilitating the process, the Cleveland Housing Network was formally incorporated in June 1981 as a stand-alone organization.

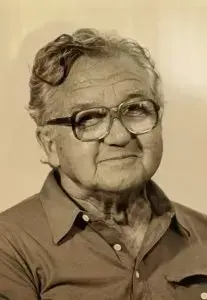

Shortly after its founding, CHN hired Chris Warren as its first Executive Director.

Warren had been a student at Hiram College on May 4, 1970, when Ohio National Guardsmen killed four students at Kent State University. Warren was a writer for the Hiram Advocate and was working on the paper at the offices of the Record-Courier in Ravenna when National Guardsmen shut down the town shortly following the shooting, closing liquor stores, cutting phone lines, and putting up roadblocks. “It showed me how quickly the power-that-be could take away your civil liberties,” Warren said. The experience had a profound impact on Warren. He immediately dropped out of college and began community organizing in Cleveland.

Warren believed deeply in Cleveland and the possibility of its neighborhoods. According to Cheryl Davis, a former colleague at Cleveland City Hall, Warren “…can dazzle anyone when he talks about the city. He can make the most unbelieving people believe this change can take place” (Crain’s Cleveland Business, April 3, 2000).

Warren described CHN as coalescing around three goals:

-

-

-

- Creating reasonable homeownership opportunities for lower-income families,

- Preserving Cleveland’s current housing stock and,

- Stabilizing Cleveland’s neighborhoods.

-

-

CHN’s first mission statement reflected these goals:

“CHN is organized to stabilize neighborhoods by saving housing and creating affordable homeownership opportunities and to promote neighborhood controlled development.”

The participating CDCs resolved from the outset that CHN would never be dependent on large institutional givers like governments and foundations for its operational funding. To keep the doors open, they built fees into the costs of the services CHN provided the CDCs.

They proceeded as a federation, working out the appropriate division of labor between CHN and the member groups. It took years to hone. CHN worked to raise capital, identify efficiencies, and advocate for greater support. The City of Cleveland supported CHN’s efforts by annually authorizing several hundred thousand dollars in Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funding.

To hear Warren tell it, CHN made a lot of mistakes in those early years, the most significant of which may have been underestimating how quickly the homes

they rehabbed would depreciate and how much more maintenance would be needed on these homes over time.

At the same time, CHN did a lot of things right. Early on, they established a relationship with the Enterprise Foundation, which had been founded in 1982 by developer Jim Rouse, CEO of The Rouse Company, and his wife, Patty, to focus the problem of affordable housing on a national level. In 1984, at Bob Wolf’s urging, BP, whose U.S. headquarters was based in Cleveland, began developing a tax syndication program that would allow corporations to invest expected taxes in not-for-profit housing. Lease-purchase arrangements were still uncommon, and it wasn’t clear at first that investors could rely on lease-purchase investments for the tax benefits they wanted. Working out the details with the Internal Revenue Service took a couple of years. Still, CHN’s lease-purchase experience and the Enterprise Foundation’s advocacy helped catalyze movement at the federal level. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 authorized the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program for the first time.

The availability of LIHTC transformed CHN’s lease-purchase program by providing it with the capital to expand. Syndicating tax credits to investors gave CHN a way to generate 60-70% of the equity it needed to purchase and rehabilitate houses and reduced the need for debt or owner equity. Rents needed to stay between $300-$600 per month to keep lease-purchase homes affordable, preferably closer to $300. However, rents had to fund all repair, maintenance, and reserves on these properties, which made funds for these projects extremely tight. There was rarely enough cash flow to take out a commercial loan on early lease-purchase projects, and when CHN faced funding gaps, it would go to the City of Cleveland with one-off requests.

As the lease-purchase program expanded, so did CHN’s need to support the families leasing their homes, so they could be prepared to purchase them at the end of the 15-year term. The same period saw CHN launch its weatherization program and begin to help lease-holders find work. By the end of the 1980s, the number of CDCs participating in CHN had more than doubled.

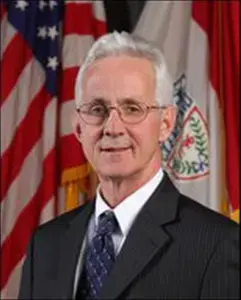

As the 1990s began, Cleveland had a new Mayor, Michael R. White, a former member of Cleveland City Council representing the Glenville neighborhood who had a background in community development. Mayor White chose CHN’s Chris Warren as his Director of Community Development, and

Mark McDermott was hired as CHN’s Executive Director. These changes signaled what would become a new, fast-growing era for CHN—which we will address in detail in next week’s post.

News & Events

View All